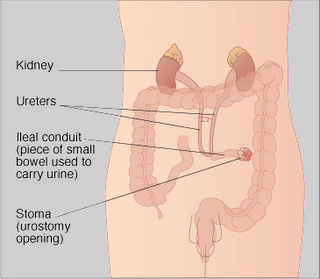

ileal conduit

A surgical procedure in which the normal flow of urine is diverted through a segment of the small bowel to a collection bag outside of the abdomen. Also called a urostomy. Ileal conduits may be performed when the bladder has been removed

An ileal conduit urinary diversion is a surgically-created urinary diversion used to create a way for the body to store and eliminate urine for patients who have had their urinary bladders removed as a result of bladder cancer or pelvic exenteration.

To create an ileal conduit, the ureters are surgically unattached from the bladder and made to drain into a detached section of ileum (a part of the small intestine). The end of the ileum is then brought out through an opening (a stoma) in the abdominal wall. The urine is collected through a bag that attaches on the outside of the body over the stoma. The bag must be periodically emptied of urine.

Indications for radical cystectomy are outlined below.

Flat in-situ transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) of bladder usually where BCG therapy has failed (T1b).

Multiple papillary tumours of bladder uncontrolled by endoscopic means (Ta, T1).

Invasive TCC of bladder (T2, T3).

Bladder TCC invading the prostate (T4a).

Squamous carcinoma of the bladder.

Sarcoma of the bladder.

This is a major procedure and the patient must be assessed for fitness, independent of age.

Admission

The patient is brought into the ward two days prior to surgery and started on a low residue diet. The stoma nurse, or similar counsellor, is booked to discuss the practical aspects of the stoma and show the patient the fitting of the appliance. The patient is shown how to change this and, after discussion, the site for the stoma is chosen below the belt line, paying particular attention to skin folds and avoiding previous scars. This site is marked with an indelible skin pencil.

On the day prior to surgery, the patient is patch tested for iodine. The patient is only permitted clear fluids to drink. Low molecular weight Heparin is given subcutaneously on the day before surgery and until the patient is mobilised and compression (TED) stockings applied.

Picolax sachets are given at 10am and again at 2pm. If there is no result, a Microlax enema can then be given (or a high phosphate enema, if the patient has not opened their bowels for several days). If the patient is frail, urea and electrolytes may be checked on the morning of surgery to identify hypokalaemia. An IV infusion may be requested overnight prior to surgery.

Where high dependency unit facilities are available, epidural analgesia is beneficial and may be mandatory if the patient has pulmonary disease. The pain team discuss analgesics. The physiotherapist instructs the patient on breathing and leg exercises. Where the patient is unfit, it is also prudent to ensure that there is an intensive therapy unit (ITU) bed available.

PROCEDURE

Antibiotics (Augmentin and Metronidazole) are given intravenously soon after anaesthetic induction. The patient is catheterised with a 16 French Foley catheter and the bladder drained. The patient is prepared using an iodine skin preparation, draped exposing the abdomen from xiphisternum to pelvis. The cross marking at the prepared site for the conduit is then transfixed with a silk or Vicryl suture, so that the mark of the site for the conduit does not become obliterated during the operation. In females, the vagina is packed with an iodine soaked swab.

Approach

The abdomen is opened. Nowadays, the patient will have previously had an abdominal and a pelvic CT scan, but it is sensible just to check that no large lesion has been missed in the liver (smaller lesions are, paradoxically, usually identified). At this stage, it is also easy to free the greater omentum. Two dry packs are used to retract the abdominal contents and a ring retractor is then placed in position.

The first approach is to open the retroperitoneal space and expose each obturator fossa in turn. Any lymph nodes are excised and sent in separate jars to the pathology laboratory.

The lymph nodes are dissected, taking all tissue medial to the genitofemoral nerve off the iliopsoas muscle and the external iliac vessels, including the fat pad at the inguinal ligament. The lymph node (Cloquet’s node) at the femoral canal, is also removed. The obturator nodes are removed and they lie between the external and internal iliac vessels The obdurator nerve is exposed, running across the picture at the end of the forceps

At this stage, it is useful to expose the ureters and place sloops around each. The bladder can then be mobilised gradually. At this stage it is possible to decide whether the bladder can be removed. If the scans are accurate, it is rare that this decision has to be reversed. Once this decision is made, the ureters can be divided at leisure. I place 2.0 Vicryl sutures around each distal end of the ureter and leave long tails. This is to allow the ureters to dilate, stops urine washing into the peritoneal cavity and the long tails allow easy identification at a later stage.

The vasa deferentes (or the round ligaments in females) are divided bilaterally (to avoid small bowel strangulation). The pedicles of the bladder can be divided, using a mixture of sharp and blunt dissection and automatic clips. The superior and inferior vesical arteries carry most of the blood supply. The pelvic fascia may be opened on either side of the bladder and Santorinis’ venous plexus divided, as one would with a radical prostatectomy. This can allow much easier mobilisation of the bladder and prostate. The parietal peritoneum over the bladder should be removed to allow the small bowel ultimately to fall into the pelvic cavity. Failure to do this can lead to a pyopelvis.

The bladder is removed and any obvious bleeding points diathermied or tied. A dry pack is then placed in the pelvis and attention is then turned to fashioning the ileal conduit. The appendix is identified and, because continent diversion is not being used, there is still a strong argument for removing the appendix, since appendicitis in patients with an ileal conduit can be very difficult to diagnose.

Ileal Conduit

The terminal ileum is then identified and a portion of ileum is isolated, avoiding the terminal 25cm of terminal ileum, which is where bowel salts are reabsorbed.

Identification of the terminal ileum

The distance can be measured. The small bowel is trans-illuminated using a satellite lamp at right angles to the bowel

Trans-illumination of mesentery aids identification of vessels

The small bowel is divided between non crushing Doyens clamps. At this stage, I find it very helpful to identify the terminal end of the conduit, by marking it with a long Vicryl suture. It is remarkably easy to get these ends reversed during a longer procedure and identification at this stage avoids difficulties later on.

The small bowel is re-anastomosed using controlled release 3.0 Nurolon (Polyamide 6 braided non absorbable, Ethicon) sutures and the window of the mesentery is repaired using interrupted absorbable sutures (2/0 Vicryl). In most cases, the small bowel sits better in an inferior position, below the anastomosis. A Backhaus towel clip can be used to approximate the Doyens clamps while the anastomosis is performed.

The distal ends of the ureters can then be identified using the long tags suture and tunnels are made so that the created gap in the posterior layer of the peritoneum acts as a window, through which the ureters are drawn The left ureter is drawn through the sigmoid mesocolon. Once again the long tags of Vicryl may be used to assist this.

Figure 5a (left) and 5b (right)

The two ureters are drawn through the window in the posterior layer of peritoneum using the long tags of sutures

The conduit is irrigated with a normal saline solution, ensuring that any remaining debris is removed.

Both ureters are joined together as the posterior layer of the Wallace I anastomosis The long tags of suture are used to secure the ureters during this and then the redundant distal ureter is excised at leisure, care being taken to ensure that the entire area remains well vascularised. If the ureters are short, a Wallace II anatomosis can be fashioned

The ends of the ureters are then spatulated and the terminal ends of Vicryl sutures can be held together until the anastomosis is partially fashioned. At this stage, size 6 Fr infant feeding tubes are passed into each ureter and drawn through the conduit

The conduit is sutured to the right side of the anastomosis and a stent is depicted in the right ureter, running through the conduit. Note the marker suture on the distal end of the conduit; this can be used to guide the conduit to the anterior abdominal wall at a later stage

The cap on the infant feeding tube is taken off the left one (shorter tube, shorter number of letters) and I found that a 3.0 Vicryl suture placed through the ureter, but not through its maximum circumference anchors the tube. The suture must of course be absorbable. Alternatively, a No. 8F single J stent may be used and does not need suturing. I use the method described by Wallace, and usually a Wallace 1.(3)

The anastomosis is then completed. At this stage, the integrity of the anastomosis is tested using 50mls of saline, injected gently with a bladder tip syringe into the distal end of the conduit. Any small leaks are sutured.

Fashioning of the stoma

The silk or Vicryl stitch on the skin, at the site of the stoma is lifted. This allows an easy excision of a circular area of skin

The suture is pulled anteriorly to allow excision of circular area of skin

A tract is then fashioned through the muscle layers (preferably through rectus abdominis to avoid parastomal hernias), into the abdomen and the distal end of the conduit is drawn through the skin. Care must be taken that there is no obstruction at this point

The stents have already been drawn through the abdominal wall and the distal end of conduit is eased through the abdominal wall using non-crushing clamps and the long suture

It is imperative that there is no tension on this anastomosis. If there is any tension or marked ischaemia, then a new conduit must be fashioned. The ends of the conduit are turned back on themselves, with four sutures 4.0 Dexon (Davis and Geck) at each corner, securing the distal end to the lower proximal area, thus everting the stoma

The anastomosis can then be dropped back into the retroperitoneum, but at this stage, the omentum is drawn down and wrapped around this area, to allow for revascularisation. Any redundant omentum is also placed near the small bowel anastomosis. At this point the attention is then turned to the pelvis again. Any residual bleeders can be dealt with at leisure.

SPECIFIC COMPLICATIONS

Apart from any general complications, occurring with any major surgery, specific complications are associated with the procedure and are listed in Table 2.

Urinary leakage

Lymphatic leakage

Ileus

Late (after 6 weeks)

Recurrent UTI

Parastomal hernia

Ureteric strictures - probably ischaemic

Stomal infarction - ischaemic

Stomal retraction

Stomal stricture

Acidosis

Bilateral hydronephrosis

Renal stone

1 Comments:

Nice post. Well what can I say is that these is an interesting and very informative topic on urostomy stoma

By Jay Fiscus, At

1:15 PM

Jay Fiscus, At

1:15 PM

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home